• Famous Harpers in the Seventeenth and Later Centuries • Turlogh O’Carolan, and His Times • Harpers of Note; Miscellaneous Mention • Harpers at the Granard and Belfast Meetings • Famous Bagpipe Makers • Famous Performers on the Irish or Union Pipes in the Eighteecnth and Early Part of the Nineteenth Centuries • Famous Pipers Who Flourished Principally in the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century • Irish Pipers of Distinction Living in the Early Years of the Twentieth Century • Famous Pipers; Miscellaneous Mention • Sketches of Some Famous Fiddlers •

CHAPTER V

Famous Harpers in the Seventeenth and Later Centuries

[p.59] THADY KEENAN

This harper, who flourished early in the seventeenth century, won immortality by his composition of that delightful air, “An Tighearna Mhaigheo,” (Lord Mayo).

The circumstances which led to its inspiration were as follows: David Murphy undoubtedly a man of genius, who had been taken under the protection of Lord Mayo through benevolent motives, incurred his patron’s displeasure by some misconduct. Anxious to propitiate his Lordship, Murphy consulted a friend, Capt. Finn, of Boyle, Roscommon. The latter suggested that an ode expressive of his patron’s praise, and his own penitence, would be the most likely to bring about the desired reconciliation. The result was in the words of the learned Charles O’Conor, “the birth of one of the finest productions for sentiment and harmony, that ever did honor to any country.” Apprehensive that the most humble advances would not soften his Lordship’s resentment. Murphy concealed himself after nightfall in Lord Mayo’s hall on Christmas Eve, and at an auspicious moment poured forth his very soul in words and music, conjuring him by the birth of the Prince of Peace, to grant him forgiveness in a strain of the finest and most natural pathos that ever distilled from the pen of man. Two stanzas will show the character of his alternating sentiments.

“Mayo whose valor sweeps the field

And swells the trump of Fame;

May Heaven’s high power thy champion shield,

And deathless be his name.“O! bid the exiled Bard return,

Too long from safety fled;

No more in absence let him mourn

Till earth shall hide his head.”

[p.64 *mention of Hugh Higgins]

OWEN KEENAN

Born in 1725 and therefore contemporary with Echlin O’Cahan, a harper named Owen Keenan, of Augher, was no less reckless, turbulent, and adventurous. Becoming enamored of a French governess at the residence of Mr. Stuart at Killmoon near Cookstown, County Tyrone, which he often visited, he proved that love laughs at other obstacles no less than at locksmiths. Blind as he was the impetuous Romeo made his way to the room of his Juliet by means of a ladder from the outside. This breach of the proprieties resulted in his commitment to Omagh jail.

Another blind harper named Higgins hailing from Tyrawley, County Mayo, who traveled in better style than most others of the fraternity, hearing of Keenan’s predicament, hastened down to Omagh, where his respectable appearance and retinue readily procured his admission to see his friend. The jailer was not at home but his wife was. She loved music and cordials and being once a beauty was by no means insensible to flattery even from men who could not see. She fell an easy victim to their wiles, and the blind harpers contrived to steal the keys out of her pocket, oppressed as she was with love and music,

They did not forget to make the turnkey drunk also, and while Higgins remained behind soothering his infatuated dupe, Keenan escaped with Higgins’ boy on his back to guide him over a ford in the river Strule, by which he took his route back to Killymoon and repeated the offense for which he had been previously imprisoned.

After narrowly escaping conviction at the County assizes, Keenan finally carried off the governess and married her. Seldom does an affair of this kind end otherwise than happily in the story books, yet rumor compels us to add that after their emigration to America, the fickle French woman proved unfaithful to her romantic Romeo.

[p.65]

HUGH O’NEILL

An honorable exception to the generality of`the harpers of his day Hugh O’Neill was a man of conspicuous respectability both in character and descent.

He was born at Foxford, County Mayo, late in the seventeenth century, and his mother being of the MacDonnell family, was a cousin to the famous Count Taaffe.

Having lost his sight by smallpox when but seven years old, he devoted himself to the study of music as an accomplishment. In later years this acquirement was turned to good account when he was beset with reverses of fortune.

From the respectability of his family and the propriety of his deportment, he was received more as a friend and associate than a professional performer by the gentry of Connacht.

To the generosity of Mr. Tennison of Castle Tennison, County Roscommon, he owed the possession of a large farm at a nominal rent. Though sightless he enjoyed a hunt with the hounds which in an open country like Roscommon subjected him to comparatively little physical danger. […and from p85 speaking about Arthur O’Neill] …Although he set out as a traveling harper at the immature age of fifteen, there is no doubt but that he subsequently received some training at the hands of Hugh O’Neill, a blind harper from County Mayo, for whom he always entertained the greatest friendship and veneration.

CHAPTER VI

Turlogh O’Carolan, and His Times

[p.75]

On another occasion, at the beginning of the eighteenth century, according to the historian Sylvester O’Halloran, the then Lord Mayo brought from Dublin the celebrated Geminiani to spend some time with him at his seat in the county. O’Carolan, who happened to be visiting his lordship at the same time, found himself greatly neglected, and complained of it one day in the presence of the foreigner. “When you play in as masterly a manner as he does,” replied his lordship, “you shall not be overlooked.” O’Carolan, whose pride was aroused, wagered with his rival that though he was almost a total stranger to Italian music, yet he would follow him in any piece he played, and he himself would afterwards play a voluntary in which the Italian could not follow him.

The test piece happened to be Vivaldi’s fifth concerto, which the foreigner played on the violin. The blind bard was victorious, and “O’Carolan’s Concerto” was the result.

CHAPTER VII

Harpers of Note; Miscellaneous Mention

[p.78…] Others of some note mentioned in Arthur O’Neil1’s Memoirs, recently published in the Annals of the Irish Harpers, by Mrs. Milligan Fox, are: “Ned” Maguire, a blind harper of County Mayo, who was drowned in the River Shannon at Limerick;

[p.79]

RENOWNED MINSTREL – CORMAC COMMON

While Turlogh O’Carolan may be regarded as the last of the Bards, Cormac Common was undoubtedly the last of the Order of Minstrels, called Tale-tellers, or Fin-Sgealaighthe.

He was born in May, 1703, at Woodstock, near Ballindangan, in the County of Mayo, although he spent many years of his adult life in the adjoining County of Galway. His parents possessed little but a reputation for honesty and simplicity of manners. Smallpox deprived him of sight before he had completed the first year of his life, so that blindness and poverty conspired to deprive him of the advantages of education. While he could not read, he could listen to those that did, and though lacking in learning, he was by no means deficient in knowledge, for a receptive mind and tenacious memory made amends for his misfortune.

Unkind fate seemed relentless, for a generous gentleman who procured him a teacher on the harp died suddenly when his protege Cormac had received but a few lessons, and so the poor blind boy’s musical prospects came to an end. His taste for poetry was still unquenched, and though too poor to buy strings for the harp, it cost nothing to listen to the songs and metrical tales which he heard sung and recited around the fireplaces at his father’s and neighbors’ houses. Having stored his memory with all he heard, and being without other means of obtaining a livelihood, he became a professional tale-teller.

At rural wakes, and in the hospitable halls of the native gentry, he found a ready welcome for his legendary tales, and being blessed with a sweet voice and a good ear, his recitations were not infrequently graced with the charms of melody. He did not recite his tales in an uninterrupted monotone, like those of his profession in Oriental countries, but rather in a manner resembling the cadences of cathedral chanting.

But it was in singing the native airs that he displayed the powers of his voice to the best advantage, and before advanced age set the seal of decadence on his vocal cords, he never failed to delight his audience. He composed several airs and songs in his native Irish language. One_a lament for john Burke, Esq., of Carrentryle—is preserved in Walker’s Historical Memoirs of the Irish Bards. `

We find that the highly romantic story of “Eibhlin a Ruin” and her elopement with Carroll O’Daly was derived from Cormac Common’s repertory.

Twice a widower, his offspring were not few, and when immortalized by Walker in 1786, he was living with a daughter near Dunmore, County Galway. In his old age he continued to be led around by a grandson to the homes of the neighboring gentry, but it would appear that with his faculties much impaired by the tooth of time, he was endured rather than admired. The date of his death is not a matter of record.

CHAPTER VIII

Harpers at the Granard and Belfast Meetings

[p.90] CHARLES FANNING

As a winner of prizes against all competitors, Charles Fanning, a native of Foxford, County Mayo, and at contemporary and rival of Arthur O’Neill, stands pre-eminent, for the excellence of his performance at the meetings of harpers at Granard, County Longford. In the years 1781, ’82, and ’83, respectively, he was awarded the first prize. This success he repeated at the Belfast Harp Festival in 1792.

Born in 1736, he was the son of Loughlin Fanning, a comfortable farmer who played well on the harp, although the instruction of the son was entrusted to at County Roscommon harper named Thady Smith.

Charles Fanning preferred Ulster to his native province, and although certain important episodes in his life happened at Tyrone, his chief haunts were in the County of Cavan. The mistake of his life was marrying the kitchen maid of one of his early patrons, a Mrs. Baillie who was a good performer on the harp herself, and who had entertained him at her table, and introduced him to genteel company. The result is well expressed in the concise language of Bunting: “He was also patronized by the celebrated Earl of Bristol, the great Bishop of Derry; but in consequence of having married a person in low life and corresponding habits, he never attained to respectability or independence.”

[p.91] HUGH HIGGINS

This distinguished harper, mentioned at some length in connection with Owen Keenan’s escape from prison, was a good performer, and outranked in social standing most of the professional harpers of his time. He was born at Tyrawley. County Mayo, in 1737. his parents being in comfortable circumstances. Blindness in early life led him to the study of the harp, and being gifted in a musical sense, he made rapid progress.

Well dressed and genteel in appearance, Higgins aimed at supporting the character of a gentleman harper, and traveled in a manner befitting the best traditions of Irish minstrelsy. He attended the Granard Balls and the Belfast Meeting in later years, but won no premiums. In fact, he did not play at all at the second hall at Granard, having taken offense at something connected with the arrangements. Arthur O’Neill’s avowed friendship for Higgins was a guarantee of his respectability.

CHAPTER XVI

Famous Bagpipe Makers

[p.159] MICHAEL EGAN

Among bagpipe makers none holds higher rank than the subject of this sketch. His name engraved on the stock of an instrument was a synonym for purity of tone and a guarantee of first-class workmanship since early in the nineteenth century.

Exact dates are unascertainable at this late day, but some leading facts in the life of this fine musician and excellent mechanic can be stated with certainty. He belonged to the town of Glenamaddy, barony of Ballymoe, County Galway, according to Mr. Burke, who associated with him in New York City. John Cummings, of San Francisco, who enjoyed his acquaintance at Liverpool away back in the fifties, says Egan hailed from the village of Cultymaugh, in the County Mayo. How he came to be a piper and pipemaker, or why he chose Liverpool instead of Dublin for his place of business, we have never learned. It goes to show, however, that Irish pipers existed in considerable numbers in England around the middle of the nineteenth century.

The famous Flannery came to America in the year 1844, or perhaps a year later. The great set of pipes which added to his fame no less than to that of Egan, who made them, he brought across the Atlantic with him. From this date we are justified in assuming that Egan had been established in business at Liverpool probably as far back as 1830, and perhaps earlier.

As stated in the sketch of John Coughlan, the so-called Australian piper, he came to America on the recommendation of the elder Coughlan, with whom he lived for some time. He kept a workshop on Forty-second Street, between Ninth and Tenth Avenues, New York, until his death, which occurred in 1860 or 1861.

The splendid set of pipes which Charles Ferguson pretended was presented to him on the orders of Queen Victoria was made by Mr. Egan in his shop in New York City during Ferguson’s visit to America.

Then no more than now was bagpipe-making and repairing a lucrative business, it seems, for notwithstanding his skill and popularity, Egan died on the threshold of poverty like that other celebrated piper and pipemaker, “Billy” Taylor, of Philadelphia. A benefit party was gotten up for him by his friends in his last illness, and Mr. Burke tells us he remained with him to the last minute.

[p.164 *] R. L. O’MEALY

[…]A native of County Westmeath, near the birthplace of O’Carolan, where his father, also a fine piper and pipemaker, was a comfortable farmer, O’Mealy traces his ancestry to the historic O’Malleys of County Mayo, where his great grandfather, Thomas, was born. The latter, though a builder by occupation, is said to have been a noted piper and pipemaker. The trade and talent passed down from father to son through four generations; and as the flattering testimonials of the press in Belfast, Londonderry, Coleraine, Newry, Dublin, and Glasgow, proclaim the excellence of his performance on the Irish or Union pipes, we are furnished with a conspicuous instance in which talent is hereditary.

CHAPTER XIX

Famous Performers on the Irish or Union Pipes in the Eighteenth and Early Part of the Nineteenth Centuries

[p.195 mention of MacDonnells of Mayo. See also Memoirs of Arthur O’Neill in Fox p.156]

JOHN MACDONNELL

[…] MacDonnell possessed several exquisite sets of pipes. One of them, made by the elder Kenna and dated 1770, Grattan Flood tells us, passed into the MacDonnell family of County Mayo and is now in the Dublin Museum on loan from Lord Macdonnell, late Under-Secretary for Ireland.

It is a most elaborate instrument, and if the date is correct it proves conclusively that the Uilleann or Union pipes had been developed into a keyed instrument with regulators much earlier than generally supposed, and certainly long before Talbot was born.

[p.206] PATRICK WALSH

Little is known of this migratory Irish piper except that he was a native of Mayo, large in stature, and flourished about the middle of the nineteenth century.

Like so many others of his profession he encouraged the belief that he was indebted to the fairies for his musical excellence.

Finding the life of a traveling piper in Ireland not to his liking, he made his Way to England, where money was more plentiful than in Connacht. Settling down in some town in Lancashire, he secured an engagement to play nightly in a barroom at regular weekly wages, and being a fine piper, even-tempered and accommodating, his employer’s increased patronage proved his popularity.

To Walsh it began to look like a life job. Yet in the midst of our joy there may lurk the germ of trouble, and so it was in this case.

One evening a gang of navvies who came in, seeing a fiddler of their acquaintance at the bar, rudely ordered the piper to put up his pipes and let the fiddler play.

Under ordinary circumstances he would be well pleased to get a rest while some other musician continued the entertainment, but the insulting tone in which he had been addressed so stirred his hot Milesian blood that he could not overlook the insult.

The herculean piper, six feet three inches in height, deliberately unbuckled his instrument and put it away carefully after detaching the bellows. With the latter as a weapon in his muscular grip he sailed into the crowd and put them to rout, fleeing in all directions for their lives.

After this incident, either from a dislike to the country or the desire to escape the penalties of the law for his onslaught, he returned to his native province, content with whatever the future had in store for him to the day of his death. He settled at Swineford, County Mayo, and taught his art to many pupils who came from near and far for instruction on the pipes.

His method of dismissing his pupils was as unceremonious as his own departure from England. When one had mastered a tune Walsh took the pupil’s hat and hung it outdoors as a signal for the owner to follow it. Without any unnecessary words another aspirant for musical learning was taken in hand and treated similarly.

CHAPTER XXI

Famous Pipers Who Flourished Principally in the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century

[p.234] JAMES O’BRIEN

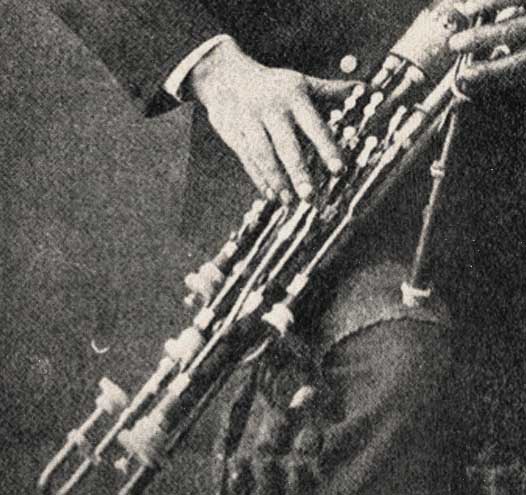

From personal knowledge the present writer can testify that “Jimmy” O’Brien was a fascinating performer on the old-style soft-toned Union pipes. We have listened to others who excelled him in execution and versatility, but no one had the faculty which he possessed of producing combinations and turns by a dextrous movement of the bottom of the chanter on his knee.

The amiable and modest “Jimmy” was born at Swineford, County Mayo, about 1823. Neither halt nor blind, he took to music through pure love of it, and, being well acquainted with Cribben, a celebrated piper, he became his pupil in early manhood. O’Brien later struck up an acquaintance with “Paddy” Walsh, another famous Mayo piper, but found him far less liberal with his tunes than the good-natured Cribben.

“Paddy” Walsh, although a good teacher of pipe music, would never allow his pupils to beat time with the foot when learning. The test of proficiency was in playing the lesson tune three times over without a slip. When this was accomplished successfully, Walsh, without a word, would pick up the pupils hat or cap and fling it out, as a hint for the owner to follow it and get the rest of the air outdoors.

After graduating, O’Brien emigrated to England, where he obtained employment in a stone-quarry in Yorkshire. An injury to his spine which he sustained at this work unfitted him for manual labor the balance of his life, so he was obliged to depend on playing the pipes for a livelihood thereafter. He played in taverns and at picnics all over the north of England, particularly in Yorkshire and Lancashire. And even wandered as far south as Devonshire on one occasion.

While sauntering along a highway one day he came to a fine-looking mansion, and, being thirsty, he went up to the hall door and rang the bell. An old lady, whose head was crowned with a wealth of snow-white hair, responded. When O’Brien announced the object of his call she asked him where he came from.

On learning that he was an Irishman she further inquired if he knew a place called Ballinamuck. Of course he did, for it was close to his birthplace. Then the mystery of her interest in Irish topography was revealed.

Her son, an officer in the English army, was killed in that vicinity a little while before the battle of Ballinamuck, in September, 1798. When the Irish and French troops were marching towards the town, followed closely by the English.

A French soldier dropped out of the ranks, too ill to proceed farther, and crawled behind a stone wall to die. Seeing the English force marching by a short time later, he took deliberate aim at an officer and shot him dead. The victim was the white haired lady’s son.

Notwithstanding a bereaved mother’s cherished grief, O’Brien’s thirst was assuaged with a beverage stronger than water.

In the early sixties he came to the United States, landing at Portland, Maine, and he played all through the Irish settlements in that state. Boston, Massachusetts, was his next destination. Having friends and relatives in Chicago, he settled eventually in the western metropolis in 1875 and made the home of Roger Walsh, whom he had known in Portland, his headquarters for a long time. Many a pleasant hour the present writer spent listening to “Jimmy’s” delightful music and memorizing his tunes, many of which were not in circulation until given publicity through our efforts.

At that time Officer William Walsh was but a strippling of fifteen, and ‘twas as good as a play to hear old Roger, his countenance aglow with parental pride, address the boy in alternate terms of encouragement, admonition and endearment as he “trebled and ground” to O’Brien’s piping.

The amiable and accommodating piper had the peculiar and oft-times embarrassing habit of suddenly stopping the music to voice a passing sentiment or indulge in conversation when elated. After his death, in 1885, his pipes were treasured by John Doyle while alive, and then passed into the possession of Sergt. James Early.

[p.244 – mention of Bartley Murphy ‘a Mayo man’ – also p.313 under Touhey]

JOHN MURPHY

Though but little known to fame the subject of this sketch was a prodigy on the pipes. Like his contemporaries. “Patsy” Touhey, “Eddie” Joyce, and many others of the fraternity, “Johnny” Murphy come of piping stock. Bartley Murphy, his father, under whose training “Patsy” Touhey’s musical talents were developed, was himself taught by James Touhey, “Patsy’s” father.

Young Murphy was a Boston boy, born in 1865. Under his father’s instruction he progressed rapidly, and soon was ranked with “Eddie” Joyce, than which no greater compliment could be paid him.

From a former companion, John Finley, the noted dancer and now promising piper. We learn that in 1885 when Murphy was but twenty years old he was matched to play against Joyce for a stake of five hundred dollars, their respective backers being Richard K. Fox of sporting fame and the renowned pugilist, John L. Sullivan. For some reason the contest never came to an issue. Quite likely Murphy’s declining health may have tended to discourage the proposition, for we are told by Mr. Finley. To whom we are indebted for the information, that he died in 1887 lamented by all who knew him.

[p.235] MICHAEL WALLACE

Born somewhere between Ballina and Westport, in County Mayo, this most celebrated of two brothers, in the opinion of some critics, rivaled the renowned William Connolly as a performer on the Union pipes. Mr. Burke says, “I have heard arguments between players about the Wallace brothers; some claimed that Michael Wallace was a better player than Connolly.” In the latter’s biography we have quoted Michael Egan as awarding him the palm of superiority as an Irish piper “on either side of the Atlantic.” As Egan, the piper and pipemaker, was a competent judge, we must regard the question of supremacy as settled.

FRANK WALLACE

All that can be said of Frank is that he was inferior to his brother Michael as an Irish piper, but at that he was an excellent performer. As far as known, they traveled together, but never extended their circuit beyond the British Isles. The Wallace brothers flourished about the middle of the nineteenth century and some years later.

The Wallace brothers and the Bohan brothers, elsewhere mentioned, had associated for years in England with a well-known if not distinguished piper-fiddler of dance hall fame in Brooklyn, New York. An appeal to that thrifty minstrel evoked promises and evasions in plenty, but no enlightenment. But perhaps we were expecting too much, with no reward in sight, from natures grown callous and avaricious by long practice in “passing the hat” on both sides of the Atlantic.

CHAPTER XXII

Irish Pipers of Distinction Living in the Early Years of the Twentieth Century

[p.284] THOMAS GAROGHAN

One of the pleasant surprises which conduced to render the Oireachtas of 1912 particularly interesting and enjoyable, was the introduction of Thomas Garoghan, the London piper, to a Dublin audience. He played on a full set of boxwood pipes, and according to one account, the performance was “splendid and refined, but the tone of his instrument was too weak to be effective in a large concert hall.” He did not have his pipes with him at the little assembly at Groome’s hotel, but on the stage of the Rotunda each evening his music was much admired, and by uttering intelligibly on the chanter, “Polly put the kettle on,” the unique trick aroused the audience to enthusiasm.

One of the pleasant surprises which conduced to render the Oireachtas of 1912 particularly interesting and enjoyable, was the introduction of Thomas Garoghan, the London piper, to a Dublin audience. He played on a full set of boxwood pipes, and according to one account, the performance was “splendid and refined, but the tone of his instrument was too weak to be effective in a large concert hall.” He did not have his pipes with him at the little assembly at Groome’s hotel, but on the stage of the Rotunda each evening his music was much admired, and by uttering intelligibly on the chanter, “Polly put the kettle on,” the unique trick aroused the audience to enthusiasm.

“Prof. Garoghan,” as he prefers to be called, was born in Coventry, Warwickshire, England, in 1845, his parents being natives of County Mayo, Ireland. He learned to play the Union pipes from James O’Rourke of Birmingham and Michael McGlynn of Aughamore, who were well known in the midland counties of England half a century ago.

Piper Garoghan is a fluent Irish speaker. Having acquired the language from his parents, and the Irishmen who come in large numbers every year to reap the English harvest; but the event which was the crowning glory of his life was his eight months’ engagement with the “Shemus O’Brien” opera company at His Majesty’s Theatre, London, some years ago. Always spry and active, he has kept the Irish pipes to the front for forty-five years, and in a country in which there was said to he an Irish piper for every day in the year less than two generations ago, he is now one of the very few remaining. He is back again in London, for after indulging a very natural desire to visit the land of his forefathers, he finds that, after all, “There’s no place like home.”

[p.296] JOHN O’GORMAN

“The blind piper of Roscommon,” born in the early [eighteen] sixties, and brought up on the DeFreyne estates, first saw the light at Ballaghaderreen, County Mayo, a few miles from the boundary line. Being blind from childhood, he began the study of the Union pipes at an early age under the tuition of Patrick Vizard, a relative, and, like many others of his class, he was unable to procure a good instrument. So superior was his skill, however, that it made amends for that drawback, and in a short time his splendid performance attracted wide attention in that part of the country.

One day, while playing at a crossroads dance, his performance so charmed Lady DeFreyne, who happened along in her carriage, that she stopped to listen to the fine music played by the blind minstrel. Drawing closer, she asked him to play a favorite Irish air. He willingly complied, and impressed her so deeply by his manner no less than by his delightful rendering of the touching melody, that she presented him with a splendid set of pipes and started him on the road to fame.

With the new instrument his popularity increased and people came from far and near to hear him. He was in great demand throughout County Roscommon to play at weddings and other festivities.

One young man now living in Chicago, named Edward Creaghton, a prize-winner in the flute contest in the Chicago Feis of 1902, who attended a wedding where O’Gorman played, thus describes the event: “I was delighted to get an invitation, for I was anxious to hear him play. When I got near the house, I could hear the strains of his fascinating music, and when I entered I beheld the famous blind piper mounted on a little stage in a corner of the room. His music was such as to set every foot in motion, for it seems no one could keep still. He had a fine set of pipes, which took up a lot of room, but there was melody issuing from every one of them, and the fine reels which he rolled out on that evening, although years ago, are still ringing in my ears.”

O’Gorman was universally respected. Whenever any event of importance was coming off, the first thing to be done was to send after him in a side car, a conveyance in which he was taken home again when his engagement was ended. Generous and liberal with his music, he played for all who asked him; in fact, his whole soul was in the beloved instrument, which responded in seeming sympathy with his touch. In close fingering and “peppering,’ he was an expert. The first prize awarded him at the Oireachtas in 1902 was no more than his due – George McCarthy and Denis Delaney getting second and third prizes, respectively. In 1908 O’Gorman did not fare so well, being defeated for first prize by Delaney.

In the long line of immortal minstrels which Hibernia has produced. “The blind piper of Roscommon” deserves a worthy place, and the province of Connacht, in which so many of them were born, shall long cherish the name of John O’Gorman.

[p.313* mentions Bartley Murphy]

PATRICK J. TOUHEY

[…]Our hero “Patsy,” when less than four years of age, was brought to America by his parents. He had not commenced to learn music before his father’s death, being then only ten years old. But he was subsequently taught by Bartley Murphy, his father’s pupil, a Mayo man, and took what may be regarded as a post-graduate course with John Egan, the “albino piper,” elsewhere mentioned.

CHAPTER XXIII

Famous Pipers; Miscellaneous Mention

[p.342]

Martin Moran was a native of County Mayo […]

[…] Not less famous was a piper named Cribben, of whom we know nothing except that he hailed from Swineford, County Mayo, and that “Jimmy” O’Brien was one of his pupils.

[p.343] Casual mention has been made of Patrick Gallagher, a capable piper of Lewisburgh, barony of Murrisk, County Mayo, who passed away in the last decade;

CHAPTER XXVI

Sketches of Some Famous Fiddlers

[p.367] PATRICK COUGHLAN

A native of Crossmolina, County Mayo, had at great reputation as a traditional fiddler in that part of the country. He must have been born about the beginning of the nineteenth century, for he was apparently beyond the scriptural age of seventy years when John McFadden knew him in his boyhood. He played with a free, sweeping bow and, notwithstanding his advanced years, this fine old musician – a type now, alas, very rare – maintained himself in comfort at the local dances and “patrons,” which in those days dispelled the monotony of peasant life in poor, persecuted Ireland.

[p.369] MICHAEL ROONEY

A professional fiddler of Ballina, County Mayo, bore a great reputation for skill and execution in his circuit in that and the adjoining County of Sligo. He was about 35 years of age when Mr. Gillan heard him in 1850. Rooney enjoyed all his faculties unimpaired.

[p.395] JOHN MCFADDEN

Long before meeting this phenomenal fiddler the echo of his praises had reached our ears, and if we chanced to express our appreciation of the playing of others in his class, some one would ask, “Did you ever hear McFadden?” This of course implied that we might save our applause until we heard this traditional star. When the opportunity was presented at the wedding of a friend in 1897, all our expectations were realized but one.

The airy style of his playing, the clear crispness of his tones, and the rhythmic swing of his tunes, left nothing to be desired, yet in the manipulation of his instrument he violated all the laws of professional ethics. His bow hand seemed almost wooden in its stiffness, and the bow itself appeared to be superfluously long, for he seldom used more than half of it.

How he came to acquire such proficiency in execution is to many a matter of surprise, still when we consider the beauty of Chinese and Japanese workmanship, accomplished with the aid of tools crude in comparison with ours, the wonder disappears.

John McFadden, now in the sixties, was born in the townland of Carrowmore, a few miles north of Westport. County Mayo. His father and brother were also fiddlers, and whatever little rudimentary instruction he got was picked up in the family. Written music was a stranger to them, consequently all their tunes were memorized from the whistling and playing of others. It is a notable fact that musicians who learn by ear and play from memory have copious repertories, while those who learn from written or printed music are usually deficient in the memorizing faculty.

The facility with which McFadden learns new tunes is only equaled by his versatility in improvising variations as he plays them. So chronic has the latter practice grown that it is a matter of no little difficulty to reduce his playing to musical notation. The following instance may serve to illustrate this peculiarity: While visiting Sergt. Early during a theatrical engagement in Chicago in 1911, “Patsy” Touhey, on the writer’s suggestion, tried to learn “Hawks’ Hornpipe” from McFadden. Phrase by phrase they progressed, Touhey submitting patiently to many minor changes according to “Mac’s” fancy, until he thought he had the tune noted correctly. Then he played it, apparently in good style, but not to his preceptors satisfaction evidently. “Let me Show you, `Patsy'” says ‘Mac,’ in a kindly tone, and swinging his bow again ran the tune over once or twice.

“Why, man alive, that’s not how you gave it to me at all! You’ve changed the tune again: I guess we’ll let it go this time,” exclaimed Touhey, as he started to play something else on his pipes.

Possessing the gift of composition as well as execution, McFadden is the author of many fine dance tunes, composed without the aid of notes or memoranda, depending altogether on his memory for their retention. Like the off-springs of O’Carolan’s brain, quite a few of McFadden’s jigs and reels were preserved by others who taught them to him over again.

An incorrigible, practical joker, many who admired his music feared his eccentricities in this respect, and, though sacrificing friendship to his whims occasionally, come what may, Democratic or Republican administration of municipal government, John McFadden always had friends numerous and influential enough to keep his name on the payroll of the city of Chicago. [More on McFadden here].

![]()